Private equity has been very popular lately. If you are a business owner wanting to sell your business, this is a prime time. Private equity funds are buying businesses with stable income, like veterinary practices, healthcare distributors, pharmacies, and accounting firms. While it might be a good time to sell, should you consider investing in a private equity fund that buys these businesses?

Private equity funds buy entire companies — or big chunks of them — in private deals. Their objective is to improve the profitability of those companies by growing them, cutting costs, or adding leverage (debt). They aim to sell the business in 5-7 years, returning the initial monies + profits to the original investors. That, in a couple of sentences, is how private equity works.

David Swensen, the former chief investment officer of the Yale University endowment fund, popularised private equity. The ‘Swensen model’ included many institutional investors (like pension funds or endowments) allocating large amounts of money to private equity. This worked well, with Swensen’s annualised return of 13.1% over his thirty-six-year tenure at Yale.

Over the last ten years, private equity (PE) has become a buzzword in finance, promising high returns and exclusive access to opportunities outside the public stock markets. This has led to an explosion of private equity funds. In 2015, private equity assets under management totalled $2.5 trillion, whereas today that figure is $5 trillion (Bain & Co estimates).

While institutional investors such as pension funds and endowments often allocate significant capital to PE, the growing push to open these investments to retail investors raises concerns. At the moment, I think it’s a case of ‘buyer beware’.

- Pass the Parcel

My concern is that if you are an existing private equity fund struggling to sell your portfolio at a decent price, you have a problem. One solution is to market these assets via a public investment fund. In other words, offload these private assets on an unsuspecting public. This process is beginning with many investment platforms offering access to ‘private markets’.

- Lack of Liquidity

Unlike publicly traded stocks, private equity investments typically lock up capital for years—sometimes a decade or more. Retail investors who may need flexibility for significant life expenses risk being unable to exit their investment when required. An investment you had hoped to exit in five to seven years may end up being locked in for a decade or more.

- Volatility Laundering

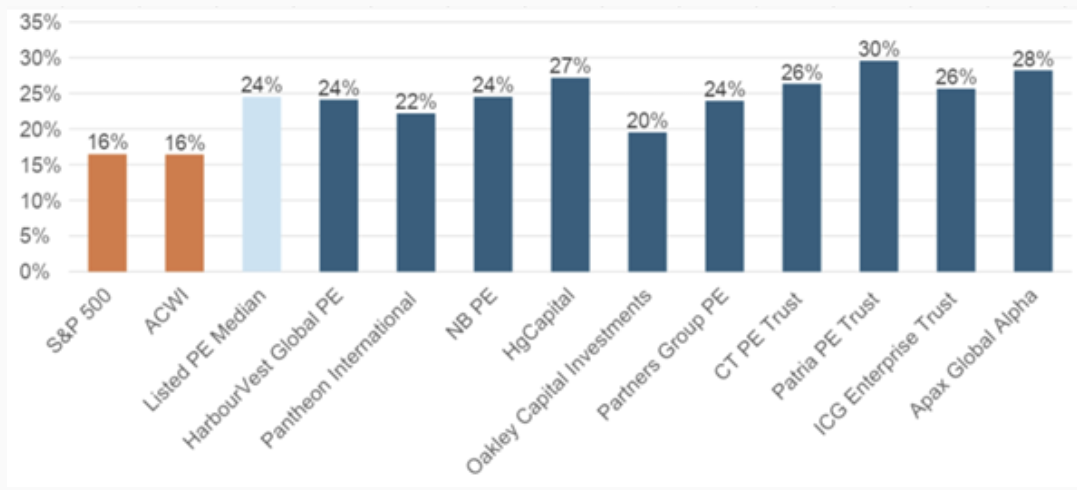

Volatility laundering, a term coined by Cliff Asness of AQR Capital Management, describes how private equity funds understate the volatility of their investment. In public markets, such as the US stock market, stock prices update continuously to reflect shifts in company earnings and market sentiment. This leads to significant volatility: The S&P 500 has exhibited approximately 19% annual volatility since 1926.

The companies within a private equity fund are typically valued quarterly, but these valuations often rely on assumptions rather than real-time market pricing. This infrequent valuation schedule creates an artificial smoothing effect, making returns appear less volatile than they actually are. This means that underperformance of a private equity fund can be masked for years, which an investor may not know.

Annualised volatility of private equity companies listed on the LSE, 2014-2024.

Source: Verdad & Capital IQ

- High Fees and Complex Structures

Private equity funds often charge the traditional “2 and 20” fee structure—2% annual management fees plus 20% of profits. These layers of fees erode net returns and are significantly higher than low-cost index funds available to retail investors. Investors in private equity sold via Irish wealth managers can pay up to 3%-4% per annum.

- Limited Transparency

Unlike public companies, private firms are not required to disclose detailed financials. Retail investors may struggle to understand the actual risks, performance, or conflicts of interest embedded in a fund’s structure.

- Risk of Underperformance

Private equity returns are significantly positively skewed. This means that while a few highly successful funds generate exceptional, outsized returns that pull the average up, many more funds produce more modest, or even negative, returns. So, it’s a ‘winner takes all’ asset class where a few select funds produce most of the investment returns.

- Unsuitable Risk Profile

Private equity is inherently high risk: concentrated bets, leverage, and exposure to cyclical industries. For retail investors without large, diversified portfolios, such risks can be devastating if outcomes fall short.

Conclusion

Private equity might suit large institutions with long-term goals and advanced due diligence skills, but it is generally not suitable for most individual investors. For retail participants, the combination of illiquidity and high costs can turn an investment opportunity into a costly mistake.

+353 (0)87 344 5882

+353 (0)87 344 5882 info@saolcapital.ie

info@saolcapital.ie Saol Capital, City Quarter, Lapps Quay, Cork T12 Y3ET

Saol Capital, City Quarter, Lapps Quay, Cork T12 Y3ET